|

Issue Three Art as a Reflection of Our Times: Art, in all its forms, can illuminate, inspire and provide a unique perspective on current events and issues that can be hard to absorb. Art reflects where and who we are, and how the world around us impacts our daily and creative lives. It holds a mirror up to the times. It reflects our hopes, desires, and the difficulties we face—individually and as a community. At a historical moment, looking at and thinking about art is as critical as ever. In this Postcard, New York Times critic, Jason Farago gives us a behind-the-scenes view, his thoughts on the issues facing the art world, such as the complexities of the recent postponing the Philip Guston Now exhibition, African art restitutions from the African vantage point, and bringing our attention to sublime works of Durer and van Dyck, giving a broader context and explanation as to why they are just as significant to viewers today as when they were first painted. All we have to do is look, read, and think as he presents all of these ideas with us in mind. Enjoy! Helen Lee-Warren Chairperson |

Jason Fargo

MA History of Art, 2007

How has the Times approached art criticism since the pandemic? What does a critic do when there’s no art to see?

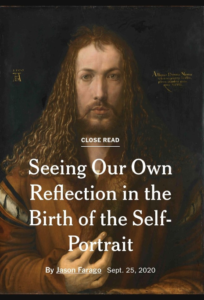

One of the first questions we had to answer was: was it now legitimate to review art from the screen? We all agreed that, some digital-only shows apart, it wasn’t — but we also believed that the domain of art encompassed more than just exhibitions. We turned our focus to all the other formats in which art finds a public, from scholarly publications to Instagram accounts. What really excited me was building a new digital story format, called Close Read, where I can examine a single work of art, such as Dürer’s Christlike self- portrait of 1500, by zooming in from detail to detail. (It’s a real throwback to my art historical training—all those days writing ekphrasis had a purpose!) Museums and galleries in New York began to reopen in September, and I’m back out there with a surgical mask on. But the Times newsroom remains closed; we’re still putting out the paper from our laptops, every day.

How do you decide what to write about?

I didn’t fully appreciate, before I joined the Times, that the real privilege of the job is not giving something a positive or a negative review. The privilege is getting to frame the discourse by saying that this show or this artist deserves your attention. You find the young artist who’s pushing against the grain, like Neïl Beloufa, who brought such a refreshing skepticism to museums’ rush to Zoom events and social media sharing. Or you look to the past to illuminate the present: in March, at the start of the lockdown, I went into the empty Met to see a Van Dyck painting of a plague saint that he made while quarantined in Palermo. Or you can think critically through interviews or round tables; when the French government completed its report on restituting artworks in the Musée du Quai Branly to various west African nations, I thought the best thing to do was to invite a Senegalese philosopher and a Nigerian artist to dinner, and let them have the floor. The goal, I guess, is to point your periscope in enough different directions to give people the full view, and definitely not to advocate for your favorite artists or places. Your duty is not to art institutions; it’s to readers.

If you could offer advice to your younger self, when you were a Courtauld student, what would it be?

Spend as much time in the gallery as you do in the library. I went often, yes, but I should have lived in there. You’ll never have another chance, outside of a museum job, to spend so much time with such a concentration of masterpieces – and for students of contemporary art, the chance to see how a collection forms, how its emphases and values change over time, is directly applicable for critics or curators or dealers of art today. And beyond that: the kind of repeated viewing that The Courtauld collection offers students is just the most fabulous gymnasium for a budding art writer. Look, look, look again, think again.

If you were not in the art world, what would you be doing?

So I have a very uncool dream job: I think I could be a very good tax inspector. I first got this idea at the Venice Biennale one year, when I noticed that right next to Cipriani is an outpost of the Guardia di Finanza, the Italian tax police, who have their own special speedboats idling in the lagoon. I thought: hmm, this could be fun. Maybe I need a second career chasing diamond smugglers in Sardinia and tax cheats in Amalfi.

Who is your favorite lesser-known artist?

If we’re talking living artists, I am a paid-up groupie for Catherine Murphy, an American painter whose intense, off-kilter observation invites the most profound thinking about how we understand what we see. She is an acquired taste but, for her small coterie of fans, she’s a kind of shared obsession. Among the dead: I am a sucker for Melchior d’Hondecoeter, the grandest animalier painter of 17th-century Amsterdam. My favorite one is at the Rijksmuseum and features a European pelican, an African crane, an American flamingo: early globalization in avian form.

If you could be anywhere in the world right now, where would it be and what would you be doing?

The answer is as obvious as it is embarrassing: JFK Terminal 4. These last few months I’ve been dreaming (I mean dreaming, literally) of airports. When the pandemic put a halt to the contemporary art world’s cavalcade of fairs and biennials and openings and conferences, a lot of my colleagues breathed a sigh of relief and, goodness knows, the climatic price of all that flying was too high. But the only thing worse than constant motion is constant stasis, and I am just about the least adept person for sheltering in place. One of the things I learned at The Courtauld was to understand art history not as a stable collection of dusty pictures and objects but as a perpetual migration of images and ideas and people, across borders, across centuries. It’s that fluidity I miss most of all right now. Meet me in the departure lounge.

Jason Farago has served as art critic for the New York Times since 2017. Before that he was the first US- based art critic for the Guardian, as well as a regular contributor to the New Yorker, Artforum, Frieze and other publications. Jason was also the editor at co-founder of the art and culture magazine Even, whose run is anthologized in Out of Practice: Ten Issues of Even, 2015–18 (Motto Books). In 2017 he was awarded the inaugural Rabkin Prize for art criticism.

Previous Postcards:

Deborah Swallow — Märit Rausing Director of The Courtauld

Bill Griswold — Director of the Cleveland Museum of Art

Jason Farago — Art Critic, The New York Times

Joachim Pissarro — Art Historian, Theoretician, and Director of the Hunter College Galleries

Sara Turner — US Department of Justice

Mary Rozell — UBS Art Collection